Hidden East Anglia:

Landscape Legends of Eastern England

THE

QUEST FOR TOM HICKATHRIFT

Part 3 - Legends in the

Landscape:

(For references, see Part 5).

1)

The Mound:

One of the most interesting adjuncts to the Hickathrift mythos was an earthen mound, which stood at the Smeeth in a field south

of the village crossroads, not far from the former Smeeth Road railway station. The first printed mention of this mound seems to be Miller and Skertchly in 1878,13 taking their information from Jonathon Peckover of Wisbech. They speak of “a mound with the marks of an entrenchment visible around it. This is called the giant’s grave, and the people of the neighbourhood have a tradition that it is hollow”.

The next reference I found quoted in G. L. Gomme’s edition of one of the chapbooks in 1884,11 the quote being supposedly taken from the ‘Journal’ of the British Archaeological Association for about the year 1869. The Society of Antiquaries in London, who hold all the back copies of the ‘Journal’, were unable to trace the passage in question for me - but very recently (2015, as I write this update) the folklorist and historian Dr. Maureen James has very kindly pointed me towards the true source. It does indeed originate in the BAA 'Journal', but from 1879, in an article entitled 'Fen Tumuli', by the above-mentioned Jonathon Peckover.12

It reads: "Another mound, close to the Smeeth Road Station, between Lynn and Wisbech, has also a traditional interest. It is

called the giant's grave, and the inhabitants relate that there lie the remains of the giant slain by Hickathrift, with the cart wheel and

axletree. The mound has not been examined. It lies in the corner of the field, with a slight depression round it, and has now only an

elevation of a few feet. A cross was erected upon it, and is to be seen in the neighbouring churchyard of Terrington St. John's,

bearing the singular name of 'Hickathrift's candlestick'."

The perplexing matter of the cross will be dealt with shortly.

Hillen8 terms it “a low tumulus (somewhat levelled on one side) with distinct marks of an entrenchment”. Dutt in 190914 considered it “an artificial mound, possibly a barrow”. As caves (occupied by ogres or otherwise) are pretty unlikely in the Marshland, I would venture that this was indeed an ancient burial mound, possibly with a visible entrance, or more likely a collapsed section, that gave people the idea that a giant lived there.

In the same field, ‘Hicifric’s’ or ‘Hickathrift’s Field’, was a rough hollow or dry pond with some form of low bank around it. A former owner of Hickathrift Farm (which still stands opposite) said in 195515 that there were two hollows “locally known as Giant Hickathrift’s Bath and Feeding-bowl”. But the pond with the bank round it was usually called ‘Hickathrift’s Hand-basin or Wash-basin’. Basil Cozens-Hardy in 193416 claimed it to be truly a “Scandinavian doom-ring”.

It seems likely that he derived this idea from the Kelly’s

‘Directory of Norfolk’ for 1925,17 where the

‘doom-ring’ was said to be “the ‘moot’ place twice each year of

the earliest inhabitants, and of their descendants down to the close of

the 18th century, of the Seven Towns of Marshland”.

Cozens-Hardy gave the added information that at midsummer the

‘commoners’ met at the earthen mound, while at Easter they gathered at

St. John’s Gate a little to the north.

The truth

of these statements I’ve so far been unable to verify. In March 1929 the

ponds were filled in with earth from the mound, and the field (in the

angle between Smeeth Road and School Road) ploughed up to make ready for

the building of council houses. On my first visit to the site in 1980 I

was pleasantly surprised to find that most of the field was still rough

and open, but things have (of course) changed since then. Now mostly built

over, only a small portion of the field remains, behind the primary

school, although the name ‘Hickathrift’s Field’ still survives.

2)

The Crosses:

Above, it

was stated that an ancient stone cross, once standing upon the

‘Giant’s Grave’ mound, had been moved to the churchyard at

Terrington St. John. Miller and Skertchly13 agree with this, as

do Porter in 196918 and various other commentators. However,

Cozens-Hardy stated in 1934 that, when soil was being carted from the

mound to fill in the ponds, “a large pedestal, 2’9” square and

1’9” high with stop-angles was unearthed. Two feet of the shaft, now

pointed, survive. The cross has been moved into the hedge next to the main

road....”

How could it be, I wondered, that a

cross which had been stated 65 years before as having been moved several

miles to another village is suddenly found in the very place it was

supposed to have been taken from?

To complicate matters, Terrington St. John actually has a portion of a stone cross also known as ‘Hickathrift’s Candlestick’, which stands just outside the north door of the church. But I have seen an old photograph of the Smeeth Cross taken just after it was rediscovered in 1929, and it is definitely not the same one.

The issue

becomes even more complex when Cozens-Hardy says of the St. John cross

that “some time in the middle of the 19th century when the

late William Cockle, who was a churchwarden of St. John’s church, gave

it to the late David Ward, who removed it to his residence in

Terrington

St. Clement, which subsequently became known as Hamond Lodge, and is now

known as Terrington Court, where it is still. It appears to consist of the

socket stone with other fragments piled upon it....”

Thus the

next question becomes: how is this cross still at St. John’s when it was

moved to St. Clement’s over a century ago? The owner (in the 1980’s)

of Terrington Court told me that “there are at least two stones in the

grounds of (the) Court that would appear to be part of a medieval

cross...One source says (they were moved) from the churchyard at

Terrington St. John, and another source says that they were brought from

the marshes having been a medieval mark at one end of a marsh

crossing...”19 But as far as he knew, the fragments had no

particular local name.

Thus the

next question becomes: how is this cross still at St. John’s when it was

moved to St. Clement’s over a century ago? The owner (in the 1980’s)

of Terrington Court told me that “there are at least two stones in the

grounds of (the) Court that would appear to be part of a medieval

cross...One source says (they were moved) from the churchyard at

Terrington St. John, and another source says that they were brought from

the marshes having been a medieval mark at one end of a marsh

crossing...”19 But as far as he knew, the fragments had no

particular local name.

~ ~

So what do we have so far? We have:

- A cross called ‘Hickathrift’s Candlestick’ that turns up at the Smeeth, when it should be at Terrington St. John.

- A cross of the same name at St. John that should be at Terrington St. Clement.

- Fragments of a cross at St. Clement, with no name, that may have come from either St. John or the marshes.

What a muddle! But hold on, there’s more to come!

~ ~

Hillen8

declares that the Smeeth Cross “is said to have been removed to Tilney

All Saints churchyard...” where it rests outside the south porch. And

indeed there is a ‘Hickathrift’s Candlestick’ in Tilney churchyard

– in fact there are two! That near the south porch leaning precariously

in its socket stone has four or five distinct indentations on the top of

the shaft which legend says are the marks of giant Tom’s fingers. They

are of course

simply the remains of mortise holes into which the tenons of the next

section of shaft were once fitted. When I first saw it, the second

cross-shaft had become detached from its base, and was propped against

the wall just inside the churchyard gate. Now (2018) it has been set

upright into a rough block, but again close to the wall. It bears upon

the shaft the weathered remains of various armorial shields.

Back to the

Smeeth Cross though. A further clue to the unravelling of the mystery

turned up in the ‘Sunday Express’ of May 14th 1950, where

the following is found: “A quaint stone monument at the bottom of Mr.

Harry Bodgers’ new council house did not please Mrs. Bodgers at all. So

Mr. Bodgers dug it up and buried it. But he didn’t know that the stone

had been a landmark in the village of Marshland Smeeth (sic), Norfolk, for

500 years. It was known as Hickathrift’s Candlestick, weighed

three-quarters of a ton, and was named after a legendary giant. Now the

Ministry of Works may be approached for an order to have the monument

exhumed”.

As far as I

know, there was no follow-up to this in the newspaper. Although I

haven’t been able to pinpoint Mr. Bodgers’ house, there seems little

doubt that this “quaint stone monument” was in fact the Smeeth Cross.

In the ‘Eastern Daily Press’ for December 12th 1964, a Mr.

Colman Green reported that the cross was still visible, and learned a new

name for it from a local farm hand: ‘Hickathrift’s Collar-stud’.

I’m pleased to say that I’ve now managed to uncover virtually the whole recent history of the Smeeth Cross (although a little must be admitted as reasonable supposition).

Prior to the mid- or late 19th century the cross was clearly visible on the summit of the ‘Giant’s Grave’ mound at the Smeeth. Then, through the action of time and weather it was covered up by earth and vegetation, and people thought it had been lost or taken away. Antiquaries, discovering that there were others known by the same name at Terrington St. John and Tilney All Saints, surmised that it had been removed to one of these two places. The 18th century historian Tom Martin recorded three churchyard crosses at Terrington St. John, and as only one is now visible, it seems likely that it was one or possibly two of these that were taken to Terrington Court.

In 1929 during clearance work

the Smeeth Cross was uncovered, still upon the mound. It was damaged by

the workmen and pushed to one side, where Mr. Bodgers’

garden was soon

to be made. He buried it in 1950, but it turns out that some time in the

‘50s or early ‘60s a part of the base was rescued and taken to the

Wisbech and Fenland Museum. There it stayed until June 6th

1979, when it was given back to the villagers of Marshland St. James and

they, in belated celebration of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, incorporated

the remaining fragment into the base of the new village sign, where it

stands to this day, at the crossroads known as ‘Hickathrift’s

Corner’.

In 1929 during clearance work

the Smeeth Cross was uncovered, still upon the mound. It was damaged by

the workmen and pushed to one side, where Mr. Bodgers’

garden was soon

to be made. He buried it in 1950, but it turns out that some time in the

‘50s or early ‘60s a part of the base was rescued and taken to the

Wisbech and Fenland Museum. There it stayed until June 6th

1979, when it was given back to the villagers of Marshland St. James and

they, in belated celebration of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, incorporated

the remaining fragment into the base of the new village sign, where it

stands to this day, at the crossroads known as ‘Hickathrift’s

Corner’.

And I hope that sorts the whole matter out for future

researchers!

3)

Tom and

the Stone Football:

The incident where Tom kicks a football out of sight has already been mentioned. But this seems to have merged, or been confused, with another episode where he throws a hammer five or six furlongs into a river. The results of this amalgamation are almost as confusing as the problem of the various crosses!

The earliest

written variant occurs in Hillen8 in about 1891 where, although

he seems unsure whether the missile is a hammer or a ball, he has altered

the furlongs into miles, and says that Tom hurled it six miles from the

Smeeth, to actually hit the church at Tilney All Saints. And, he says,

“the credulous villagers still point out the actual spot, in the

chancel-end of their church, where the hammer (or ball) struck the

wall....”

Only a year later in 1892, Murray,20 speaking of the church at Walpole St. Peter, says “there are two circular holes in the north and south walls of the chancel opposite to each other, which tradition says were made by a ball kicked by (Hickathrift)....” So, already we have a divergence in the tales.

In

1955 Mr. W. S. Parsons21 adds another dimension, by reporting

that Tom “announced that he would kick a stone ball and that wherever it

fell he would be buried. He kicked the ball from Tilney St. Lawrence and

it hit the wall of Tilney All Saints church, roughly two miles away. The

impact caused a crack in the church wall which, it was said, could not be

permanently repaired....”

Next with a

variant is T. C. Lethbridge in his 1957 book ‘Gogmagog’.22

He announces that Tom “threw a missile...through the wall of Walpole St.

Peter’s church, where a small hole is still shown....” In 1966 Randell

and Porter23 say that Tom threw a stone three miles from a

river to Tilney All Saints, and was buried where it fell. From the same

source comes the claim that Tom beat the Devil in a game of football in

the churchyard at Walpole St. Peter, but during the match Satan kicked the

stone ball at our hero, missed, and the ball went through the church wall.

A compendium of legends in 197324 gets the notion that Tom

actually fought the Devil at Walpole, from where Roberts25

probably originated his claim that “Tom wrestles the Devil...and

wins”.

Once again we seem to have two parallel traditions arising from one or two similar incidents in the early chapbooks, but this time they may be roughly coeval. The vagueness of the targets in the ball-kicking and hammer-throwing episodes is, I think, sufficient to account for the basic variations. Also at Walpole, the two small round holes are probably where the ends of vanished tie beams of the church structure protruded through the walls.

~ ~

But at Walpole St. Peter there is another object, which I think served to attract the associations with Tom the giant.

The first reference to it is in

Murray in 1892,20 where he mentions “a figure of a satyr

supposed to be Roman, called by the

country people ‘Hickathrift’, the

traditional local giant, (which) is built into the outer wall at the

junction of the chancel and north aisle....” Roberts25 is

overstating things somewhat when he calls it “a monstrous, carven stone

giant’s effigy (a la Cerne Abbas)....” as the little figure is only

21” high from head to toe!

It is a very weathered image of crumbling

sandstone on the north side of the church, and stands upon a corbel

supporting a rood-stair window. Its identification with Hickathrift is

somewhat suspect though, as it is of very indeterminate sex. Indeed, the

architectural historian Pevsner26 calls it “a small caryatid

figure, probably Roman”. The point being that a caryatid is a female

figure used as a pillar or support.

4)

Hickathrift’s Grave:

If we

assume then that the Walpole incidents are but variations on a basic

theme, we’re left with the fundamental action, common to many

folk-tales, of the hero standing somewhere (probably the Smeeth), and

throwing or kicking a stone for some distance, saying that where it lands

he wants to be buried. And in this case, the burial site is confirmed by

almost every writer from Weever in 1631 onwards as being the churchyard at

Tilney All Saints.

From about

the 1950s, the inquisitive tourist has been shown a stone in the

churchyard that is claimed to mark the grave of Tom Hickathrift the

giant. It lies a few feet from the east end of the church, and is a simple plain slab of unadorned granite on an

east-west axis, whose exact shape (when I first saw it) was hard to discern

because of the dense undergrowth around and over it. Now, it has been

cleared, and has been labeled as an aid to visitors. There have been

various estimates of the stone’s length over the years, such as “no

more than seven feet”,24 “nearly eight feet”,27, 28

and “eight feet long”.18, 25

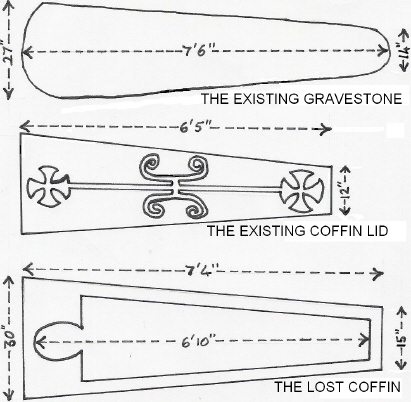

Having accurately measured it,

I can safely say that the stone was originally exactly 7’6” long, but

now has a 3” split across the middle that has forced the two halves

apart. This is supposed to be the very stone that Hickathrift threw from

all those miles away.

However, if we go right back to 1631

and John Weever, we find: “In the churchyard is a ridg’d Altar, Tombe

or Sepulchre of a wondrous antique fashion upon which an Axell-tree and a

cart-wheele are insculped; Under the Funerall Monument, the Towne-dwellers

say that one Hikifricke lies interred”. Likewise Dugdale in 16625

refers to the gravestone “whereupon the form of a cross is so cut as

that the upper part thereof by reason of the flourishes...sheweth to be

somewhat circular, which they will, therefore, needs have to be the wheel

and the shaft the axletree”.

How then is it that the present

gravestone bears no resemblance whatsoever to this earlier carven ‘Sepulchre’?

As they say in all the best exposés, now at last the full story can be

told!

The main point is that up to about 1810 the grave was complete – that is, consisting of both a coffin and a coffin lid or cover, but after that date the two had become separated. In 1803, Blomefield4 describes “the stone coffin” and the sculptured lid together. By the time of Sir Francis Palgrave’s investigation around 181429 things had changed. He ascertained “the present state of Tom’s sepulchre. It is a stone soros (coffin), of the usual shape and dimensions; the sculptured lid or cover no longer exists”.

Exactly where it had gone at that time I

don’t know, but it certainly existed then and still does. In 1883 along

came William White30 who noted: “In the churchyard is part of

a stone coffin, said to have contained the remains of Hickathrift....”

Note the

words “part of a stone coffin” - because Hillen in 1891 also uses them:

“Until recently a part of a stone coffin, said to contain the remains of

the Fenland hero, might have been seen to the north of the church. It

measures 7’4” outside, and

6’10” inside; whilst the breadth at the

head was 2 ½ feet, and at the feet 1’3”....” But he also mentions

the lid having been “deposited at the west end of the north

nave-aisle”, actually within the church itself. The following year

Murray20 (quite possibly just taking his cue from Hillen) also

says that “here until recently (it is now moved into the church, at the

west end of the north nave aisle) was a grave slab with a cross and circle

round it....”

6’10” inside; whilst the breadth at the

head was 2 ½ feet, and at the feet 1’3”....” But he also mentions

the lid having been “deposited at the west end of the north

nave-aisle”, actually within the church itself. The following year

Murray20 (quite possibly just taking his cue from Hillen) also

says that “here until recently (it is now moved into the church, at the

west end of the north nave aisle) was a grave slab with a cross and circle

round it....”

From then until Parsons in 195521 only this

coffin lid inside the church is ever mentioned, but Parsons is the first

to commit to print the existence of the current gravestone. It will be

noticed in the accompanying drawings that not only do none of the items

conform to the eight-foot stature of the chapbook giant, but also that

none is exactly the same size as the others.

What seems

to have happened is this: from the early days of the 17th

century, there was a large stone coffin with a curiously ornamented lid

that was associated with the burial of the legendary giant Tom

Hickathrift. Some time afterward the coffin and lid became separated, and

the coffin vanished from sight  (buried, broken up, who knows?) But there

must have been a second (perhaps lidless) coffin, even larger, that came to be thought of as the giant’s. I say must

have been, because the coffin as described by Hillen (7’4” long

outside) is far too large for the 6’5” lid to have fitted it.

(buried, broken up, who knows?) But there

must have been a second (perhaps lidless) coffin, even larger, that came to be thought of as the giant’s. I say must

have been, because the coffin as described by Hillen (7’4” long

outside) is far too large for the 6’5” lid to have fitted it.

I have it

on expert advice31 that the lid should have “fitted it (the

coffin) exactly. Usually most coffins and their lids were carved at the

same quarry and transported as a single order. I would expect an entirely

different lid to cover (this) coffin...”

Around the 1880s this larger coffin was breaking up, and ten years later it had vanished completely, the carved lid having been taken inside the church for safekeeping. Thus, sometime in the first half of the 20th century, a massive slab of granite was found or made, and placed over the remains of whoever it was that was thought to be the giant. Indeed, because it matches to within two inches the length of the coffin, it may have been specifically tailored to suit the conditions of the legend.

But whichever the case may be, the gravestone that people are now shown as being Hickathrift’s is no more than a relatively modern replacement, perhaps no more than 80 or 90 years old.

~ ~

Now, what

about those odd carvings on the coffin lid? They are done in relief, and

much weathered, but all the designs can still be seen quite clearly –

which is more than can be said for the days of Weever et al, since they

consistently mention only one “round cross upon a staff”. This is what

Blomefield had to say on the subject in 1808: “the cross, said to be a

representation of the cart-wheel, is a cross-pattée on the summit of a

staff, which staff is styled an axle-tree; such crosses-pattée on the

head of a staff, were emblems, or tokens, that some Knight Templar was

therein interred, and many such are to be seen at this day in old

churches”.

One or two

antiquaries agreed with this observation, with Gomme32 even

going so far as to speak of “one Hickafric, supposed to be a Knight

Templar”! However, according to my expert advice31 “there

is no evidence that the crosses pattée denote a Templar grave”. The

central design, the four curving arms, “it has been suggested were

intended to represent the scarves or infulae attached to processional

crosses. From the shape of this device the cumbrous name of

‘Omega-slabs’ has been given to them, and their area of

distribution...suggests that they were products from the Midland

quarries”33 This Omega pattern is, apparently, quite common

in eastern England.

If we assume that neither the large coffin, the lid, nor the granite slab actually held or covered the remains of a legendary giant, then just whom did they hold or cover?

Part 1 - The Land of the Giant

Part 2 - The Tales & their Sources