Hidden East Anglia:

Landscape Legends of Eastern England

THE

QUEST FOR TOM HICKATHRIFT

Part

2 - The Tales &

their Sources:

(For references, see Part 5).

The earliest printed mention of the giant Hickathrift occurs in a massive book by John Weever, entitled ‘Ancient Funerall Monuments’, dated to 16311. Weever reports a tradition of the Smeeth that once upon a time, a great conflict broke out between the inhabitants of the Seven Towns and their Landlord, over the rights and boundaries of the Smeeth, and the villagers were definitely getting the worst of the battle. At this time, Tom had got himself a job carting beer for a King’s Lynn brewer, and he often had to drive his cart over the Marshland to Wisbech.

Along comes Tom to the scene of the battle and, in Weever’s words, “perceiving that his neighbours were faint-hearted, and ready to take flight, he shooke the Axell-tree from the cart, which he used instead of a sword, and tooke one of the cart-wheeles which he held as a buckler; with these weapons....he set upon the....adversaries of the Common, encouraged his neighbours to go forward, and fight valiantly in defence of their liberties; who being animated by his manly prowesse, they....chased the Landlord and his companie, to the utmost verge of the said Common; which from that time they have quietly enjoyed to this very day”.

Later antiquarian writers such as Spelman in about 16402, Cox in 17203, and Blomefield in 18084 follow Weever almost to the letter, apart from Dugdale5 who is the ‘joker in the pack’, and who will be mentioned again shortly. However a significant divergence in story line occurs in the early chapbooks, those slender pamphlets for consumption by the ‘peasantry’ that pedlars hawked on the village streets. The earliest still in existence is in the Pepysian Library at Cambridge, printed between 1660 and 1690, and bearing the title ‘The History of Thomas Hickathrift’.6

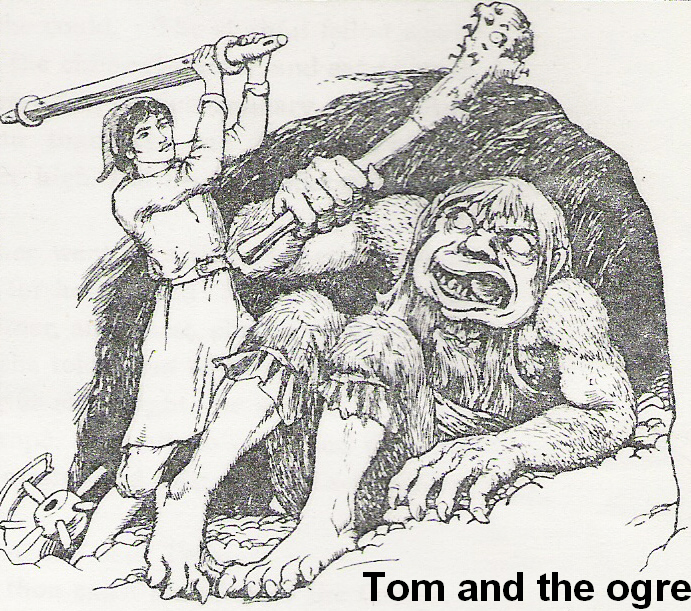

This chapbook relates how Tom used to drive his brewer’s cart between Lynn and Wisbech, but because of a fierce giant or ogre that dwelt in the Marshland, had to make a long detour around. One day Tom became fed up with this, and on his next journey resolved to test the ogre’s might. From his cave, the giant saw Tom coming and leapt out to meet the trespasser, saying “Do you not see how many heads hang upon yonder tree that have offended my law! But thy head shall hang higher than all the rest for an example”. To which Tom then gave the classic riposte “A turd in your teeth for your news, for you shall not find me like one of them”.

The giant, enraged, dashed back into his cave for his gigantic club, while Tom up-ended his cart and took the axle and wheel for a sword and shield. With these weapons, and after a mighty battle, Tom beat the twelve-foot high ogre into the ground and sliced off his head. After this deed Tom became the hero of the Marshland, and was henceforth known to all as ‘Master’ Hickathrift (a formerly distinct title that lost its significance in the 17th century).

These two

alternate themes – the defeat of the Landlord and the slaying of the

giant, both with wheel and axle – parallel one another until about the

beginning of the 20th century, when the Landlord version is

forgotten and only the giant-slaying remains. The problem is, which

tradition came first, or were there from the very beginning two separate

but very similar tales existing concurrently?

From experience I would say that the former is the true problem, and that easily solvable. Although the 17th century Pepysian chapbook is the oldest extant, we can be fairly certain that there was an earlier original, probably of the 16th century – or at least the internal literary evidence seems to point that way. And of course the substance of the chapbook is derived from popular oral tradition of indeterminate age, as is the substance of the passage in Weever.

~ ~

But it is the process of folklore to embellish, to enlarge, and thus it is that the tyrant Landlord must have come first, to be enlarged and aggrandised in the popular mind and by the chapbook writers, catering to a less discerning audience than that held by such as John Weever. For the same reason the Landlord has vanished from current Hickathrift tradition, leaving only the wicked giant to be overcome by our hero.

At this

point Sir William Dugdale should be mentioned again, because of the

curious role reversal that he creates in his 1662 work ‘The History of

Imbanking...’.6 Dugdale somehow manages to twist the Weever

story about, making Hickathrift himself into the zealous owner of the

Smeeth common land, mightily defending himself with wheel and axle against

the quarrelling villagers. This is a most peculiar reversal, and can only

be explained by a hasty and inaccurate reading of the legend as told by

Weever.

Whilst the antiquarians have no more

to say about Hickathrift’s exploits, the chapbooks on the other hand

have a great deal more to tell. After his slaying of the Marshland ogre,

Tom went into the cave and found there all the  monster's ill-gotten

hoard of gold and silver, enough to make him a rich man for life. “Tom

took possession of the giant’s cave”, says the chapbook, “by consent

of the whole company, and every one said he deserved twice as much more;

Tom pulled down the cave, built him a fine house where the cave stood; and

the ground that the giant kept by force and strength, some of which he

gave to the poor for their common, the rest he made pastures of and

divided the most part into tillage, to maintain him and his mother Jane

Hickathrift”.

monster's ill-gotten

hoard of gold and silver, enough to make him a rich man for life. “Tom

took possession of the giant’s cave”, says the chapbook, “by consent

of the whole company, and every one said he deserved twice as much more;

Tom pulled down the cave, built him a fine house where the cave stood; and

the ground that the giant kept by force and strength, some of which he

gave to the poor for their common, the rest he made pastures of and

divided the most part into tillage, to maintain him and his mother Jane

Hickathrift”.

He then

made a deer park round about, and near his house built a church of St.

James “because he killed the giant on that day....” (which at the time

of writing was August 6th). Whether or not this part of the tale

influenced the naming of the parish in 1923 I do not know, but perhaps it

is significant that there has never been another church of St. James in

the whole of the Fenland district.

With his

newfound wealth and respectability, Tom traveled far and wide throughout

the Marshland, sometimes with his pack of hounds, to such festivities as

“cudgel-play, bear-baiting, foot-ball, and the like”. One such event,

although a minor one in the course of the story, will be seen to gain a

greater significance later on. He rode one day to where some men were

laying wagers upon a football game, but he was a stranger to them and not

allowed to join in; “but Tom soon spoiled their sport; for he meeting

the foot-ball, took it such a kick that they never found their ball more;

they could see it fly, but whither none could tell....” The participants

became angry at this, but Tom simply grabbed up a “great spar” from a

ruined house, and flattened the lot of them.

On his way home he encountered four armed robbers. Once more in summary fashion he slew two and wounded the others, taking £200 from them for his trouble. But he later came upon a stout tinker barring his path, and since neither would yield to the other, they battled with staves (reminiscent, of course, of the meeting between Robin Hood and Little John). They were evenly matched, until Tom threw down his staff, invited the tinker to his home, and they became the best of friends.

~ ~

At this

point the earliest chapbook versions end, but later versions have a second

part attached, obviously written by someone familiar with the original

text, but equally clearly of a much later date. A typical example of this

would be ‘A Pleasant and Delightful History of Thomas Hickathrift’,

printed around 1750. Many others were produced all through the 18th

and 19th centuries, but all apparently based on the text of

this one. (Norwich Central Library had dated this particular chapbook to

the 1600’s, but by study of the internal evidence I revised this to the

mid-18th century, a revision that has been accepted).

This

continues the exploits of both Tom and the  Tinker (whose name was given as

Henry Nonsuch), telling how they were called to the Isle of Ely to help in

putting down a rebellion. They defeated 10,000 (one reference says 2000)

men all by themselves with naught but clubs as weapons; and when Tom’s

club broke, he “seized upon a lusty, stout raw-boned miller, and made

use of him for a weapon, till at length he cleared the field....” The

King was so pleased with them that he promptly knighted Tom, and gave the

Tinker a pension for life. As Sir Thomas Hickathrift, he then turned for

home, only to find his aged mother dying.

Tinker (whose name was given as

Henry Nonsuch), telling how they were called to the Isle of Ely to help in

putting down a rebellion. They defeated 10,000 (one reference says 2000)

men all by themselves with naught but clubs as weapons; and when Tom’s

club broke, he “seized upon a lusty, stout raw-boned miller, and made

use of him for a weapon, till at length he cleared the field....” The

King was so pleased with them that he promptly knighted Tom, and gave the

Tinker a pension for life. As Sir Thomas Hickathrift, he then turned for

home, only to find his aged mother dying.

After this

Tom’s thoughts were turned towards marriage, and he began to court a

“rich young widow” of Cambridge named Sarah Gedyng. After trouncing a

rival in love, Tom came up against two hired Troopers whom he simply

tucked under his arms until, humiliated, they swore never to trouble

anyone again. But even as Tom rode to his wedding, along came his rival

with 21 hired ruffians to stop him – to no avail, for Tom just took up a

sword and sliced an arm or a leg off every one, then hired a nearby

farmer’s dung-cart to carry them home.

An amusing

and rather bizarre episode followed at his wedding feast, which was held

in his own home. At the end of the proceedings he discovered a silver cup

to be missing, which was presently found on an old woman named Strumbolow.

While the other guests were all for chopping her to pieces for her theft,

Tom devised a rather novel method of punishment: “He bored a hole

through her nose, and tied a string thereto, then tied her hands behind

her back, and ordered her to be stript naked, commanding the rest of the

old women to stick a candle in her fundament, and then lead her by the

nose through the streets and lanes of Cambridge, which comical sight

caused a general laughter”.

Not long

after this, word came to the King that a foul giant, with many great bears

and lions in attendance, had invaded the Isle of Thanet in Kent, and posed

a dire threat to the rest of his Kingdom. Without more ado he made Tom the

Governor of Thanet, and Tom went off to combat the invader, a far more

terrible ogre than any he had faced before. For the giant was “mounted

upon a dreadful dragon, beating upon his shoulder a club of iron; having

but one eye, which was placed in the middle of his forhead, and larger

than a barber’s bason, and seemed to appear like a flaming fire; his

visage was grim and tawny, his back and shoulders like snakes of

prodigious length, the bristles of his beard like rusty wire....”

Nevertheless it didn’t take Tom long to deal with his opponent, first of

all running his “two-handed sword of ten feet long in between the

giant’s brawny buttocks, and out at his belly....and then pulling it out

again, at six or seven blows he separated his head from his trunk....”

With no more ado he suffered the dragon likewise, then he and Henry the Tinker went out and dispatched the rest of the ravening beasts. But alas! The Tinker was slain by one of the lions. Tom then went home, but died in less than three weeks out of grief for his friend. And there the chapbooks end their tale.

~ ~

But the

legends do not end, and more is added over the years, enlarging and

twisting various episodes, until much is scarcely recognisable. Probably

one of the earliest additions is related by H. J. Hillen in about 1891. A

local of the Smeeth told him that when Tom had slain the Marshland ogre,

he decided to cut out the giant’s tongue. Then shortly after Tom had

departed, along came  a rogue who severed the head and took it to the King

for a reward. Just as the King was about to open the royal purse, up

popped Tom with the tongue and claimed the reward for himself. “The

imperdant rarscal”, said the old local, “rushed scraamin’ away,

getting’ a jolly sight more kicks than ha’pence!”8 This

additional fragment is not original to the neighbourhood however, being

simply a variant on the old folk-motif of ‘The False Claimant’.

a rogue who severed the head and took it to the King

for a reward. Just as the King was about to open the royal purse, up

popped Tom with the tongue and claimed the reward for himself. “The

imperdant rarscal”, said the old local, “rushed scraamin’ away,

getting’ a jolly sight more kicks than ha’pence!”8 This

additional fragment is not original to the neighbourhood however, being

simply a variant on the old folk-motif of ‘The False Claimant’.

The earliest incident in the chapbooks, by which Tom’s great strength is revealed, is when he hoists onto his shoulder a colossal weight of straw, far more than any other man can carry. This has been altered in oral tradition so that, for a joke, the bundle of straw has huge rocks hidden inside it, but Tom still lifts it without fuss. Likewise, the four armed robbers that he dispatches become in the tales a large band of highwaymen whom he drives out of East Anglia. The chapter where Tom kicks a football out of sight has gained a wider audience, so that a Suffolk man can tell, in 1965, of “Old Icklethrift”, who kicked a ball “from Beccles to Bungay”.9 One source doesn’t like the idea of our hero dying from grief, so makes him simply return home, “where he passed the remainder of his days in great content....”10

Part 1 - The Land of the Giant

Part 3 - Legends in the Landscape