|

Puddingstone Track

Deconstructed:

Contents |

|

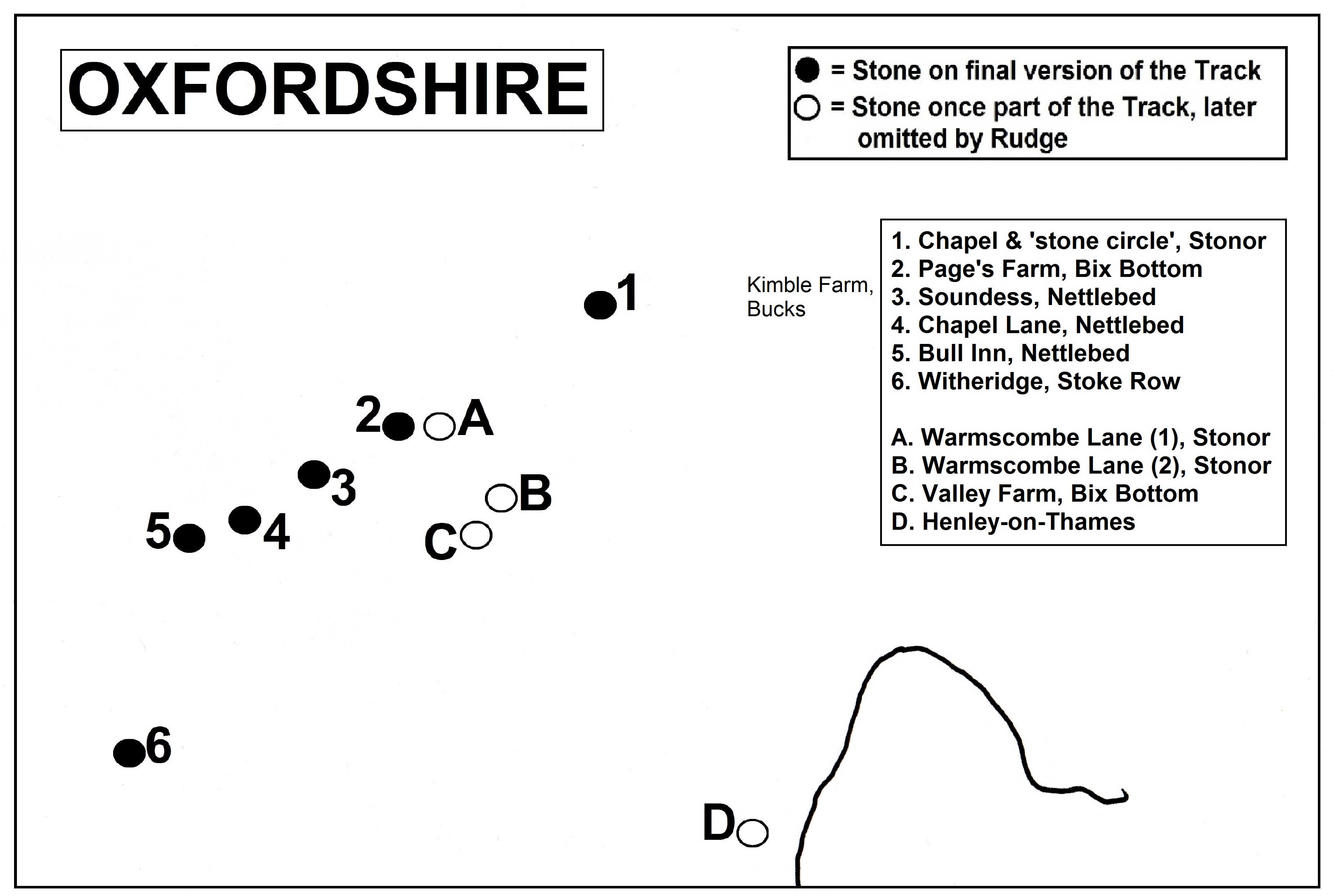

Along the Track: OXFORDSHIRE

Stonor (Pishill)

"Stonor chapel stone and

stone circle" (first mention 1955):

In June 1955 Dr. Rudge

received a letter that led him to revise the projected course of his Track.

In earlier years he had been thinking that at some point after the Kimble

Farm stone it would turn more southerly and possibly head for Henley, where

there was a puddingstone of which he'd known since 1949. The letter was from

Major Ralph Sherman Stonor, 6th Baron Camoys, of Stonor Park, two-thirds of

a mile west of the farm. The major told him that "The Chapel at Stonor has a

large puddingstone incorporated in the foundations, and there is a stone

circle a few yards away." Rudge commented that he hadn't yet checked it out,

but this information seemed to help clarify the "hitherto obscure section"

heading towards the Thames.1

The private chapel is

attached to the southern end of the east wing of Stonor House, and was built

in the 13th century (although guide

books

like to say that it's older, and Rudge claimed it as Saxon.) Small chunks of

sarsen and conglomerate are built into the fabric, but it is the large

boulder of puddingstone at the south-east corner (bottom left in the photo)

that - quite literally - sticks out (SU7429789189.) It protrudes by about

30cm just above ground level on both the eastern and southern sides, not

unlike the odd stone at Broomfield church in Essex. This is the closest

corner to the 'reconstructed' stone circle about 55m to the south, leading

many to assume that it was part of the 'original' circle. Indeed, the owners

of Stonor Park claim - without evidence - that the chapel actually stands on

that original site, advancing the frequently-repeated (but inaccurate) line

that Pope Gregory told his 7th century missionaries to build their churches

on pagan sacred sites. books

like to say that it's older, and Rudge claimed it as Saxon.) Small chunks of

sarsen and conglomerate are built into the fabric, but it is the large

boulder of puddingstone at the south-east corner (bottom left in the photo)

that - quite literally - sticks out (SU7429789189.) It protrudes by about

30cm just above ground level on both the eastern and southern sides, not

unlike the odd stone at Broomfield church in Essex. This is the closest

corner to the 'reconstructed' stone circle about 55m to the south, leading

many to assume that it was part of the 'original' circle. Indeed, the owners

of Stonor Park claim - without evidence - that the chapel actually stands on

that original site, advancing the frequently-repeated (but inaccurate) line

that Pope Gregory told his 7th century missionaries to build their churches

on pagan sacred sites.

Dr. Rudge came here at

least twice, in the 1950s and again in 1960. When he first saw the circle he

said that it was very overgrown, but after he explained its significance to

Major Stonor, it was "cleared and exposed." At that time it seems that the

stones were a little closer to the main house. Sources say variously that it

was reconstructed in its present position (SU74318913) in either 1975 or

1981. But as Major Stonor died in 1976, the work was probably begun by him

and finished by his son, the 7th Lord Camoys. An article published in April

1981 quoted him on the subject: "There can't be many people who have

reconstructed a stone circle on their property in the last few years".2

And in the same month from a local newspaper: "It has been the main work

during the winter season, Lord Camoys said".3 The park had been

opened to the public for the first time two years earlier.

The

relevance of the circle to this study of the 'Puddingstone Track' is that

Rudge claimed it is composed of alternating sarsen and conglomerate

boulders, which is not so today, nor was it when Rudge saw it. Sarsens

greatly outnumber conglomerates on the site. Virtually all the stones now

forming the ring are sarsen, but with three small puddingstones surrounded

by seven sarsens in an odd off-centre 'huddle'. Plus, there are two sarsens

and four puddingstones forming a curious 'extension' at the north edge of

the circle. An article in 'Country Life' magazine of May 7th 1981 apparently

contains a claim by the Stonor family that the circle has been reconstructed

"as near as possible in its original formation".4 If so, it bears

little resemblance to any authentic prehistoric monument. The

relevance of the circle to this study of the 'Puddingstone Track' is that

Rudge claimed it is composed of alternating sarsen and conglomerate

boulders, which is not so today, nor was it when Rudge saw it. Sarsens

greatly outnumber conglomerates on the site. Virtually all the stones now

forming the ring are sarsen, but with three small puddingstones surrounded

by seven sarsens in an odd off-centre 'huddle'. Plus, there are two sarsens

and four puddingstones forming a curious 'extension' at the north edge of

the circle. An article in 'Country Life' magazine of May 7th 1981 apparently

contains a claim by the Stonor family that the circle has been reconstructed

"as near as possible in its original formation".4 If so, it bears

little resemblance to any authentic prehistoric monument.

The antiquary John Leland

visited Stonor in the period 1535-43. Although keen to record all items of

archaeological interest, he made no mention of any stone circle nor a

prehistoric structure of any kind at the park.5 According to the

'Country Life' article, the circle had first been reconstructed in the 17th

century. Although the word 'puddingstone' hadn't come into use by then, it

was such rocks that the naturalist and antiquary Robert Plot was referring

to in 1677, when he wrote: "After consideration of Flints and Pebbles apart,

let us now take a view of them jointly together, for so I found them...in

the way from Pishill to Stonor-house in clusters together of diverse colours,

and united into one body, by a petrified cement as hard as themselves...But

the best of all are in the close at Stonor".6 Again, there was no

mention of the rocks being in a circle.

According to Dr. Rudge,

"The authenticity of the stone circle was confirmed by its inclusion on a

17th century map of the district, and also by an oil painting of the same

age, hanging on the wall of the lounge in Stonor House. In this, it is shown

as a complete circle of small standing stones, situated immediately before

the entrance to the house".7 There are problems with this

statement. Firstly, the painting. It dates from 1680-90, and hangs on the

east end wall of the Drawing Room. It's reproduced in the official guide to

Stonor Park, and shows no boulders at all, let alone in a circle right in

front of the house. Secondly, the map. There is no 17th century map of

Stonor. The earliest known is an estate map of 1725-6, which is framed and

hangs in the Study. It too shows no stone circle.8

A field visit by an

archaeologist in 1960 revealed the existence of a photograph in the family

archive dating to c.1873 which shows the stones at approximately SU74288917.9

This is about 25m NNW of where they are now, closer to the house and chapel,

and probably where Rudge saw them in the late 1950s. Another source says

that at this location, they were actually lining the rim of a pond.10

This may be why they were in a roughly circular formation at that time.

Other sarsens, some standing, some recumbent, are scattered about the

grounds near the house and along the drive.

This whole region on the

dip-slope of the Chilterns is known for both sarsen and puddingstone. Even

the name Stonor is generally believed to derive from the Anglo-Saxon 'Stān-ōra',

meaning the stony ridge or slope. In the form 'Stanora-lege' it

appears in a land charter dated 774 (which is now known to have been forged

in the 11th century), although the place referred to was probably a little

to the west of the present park. The Stonor family have held the estate for

perhaps 700 years, and it wouldn't surprise me if, in the antiquarian zeal

of the 17th or 18th centuries, one of the landowners had indeed created a

circle out of the scattered boulders. But the current structure is certainly

an archaeological 'folly', and the presence of a puddingstone in the chapel

fabric does nothing to help prove the former existence of a genuine stone

circle.

1. E.A. Rudge: 'Further

Observations on the Conglomerate Track' in 'Essex Naturalist' Vol.29, part 4

(1955), p.258.

2. 'The Catholic Herald',

17/4/1981, p.10.

3. Ray Bryant: 'The stones

of Stonor' in 'Reading Evening Post', 9/4/1981, p.13.

4. Oxfordshire Historic

Environment Record, HER No.2064.

5. John Leland: 'The

Itinerary of John Leland' Vol.5 (ed. Lucy Toulmin Smith, 1910), p.72.

6. Robert Plot: 'The Natural

History of Oxford-shire' (Oxford, 1677), p.73.

7.

E.A. Rudge (ed. John Cooper): 'The Lost Trackway' (1994),

p.7-8.

8. John Steane: 'Stonor - A

Lost Park and a Garden Found' in 'Oxoniensia' Vol.59 (Oxfordshire

Architectural & Historical Society, 1995), p.450-1.

9. Oxfordshire HER No.2064,

field notes of C.F. Wardale, 1960.

10. Steane: op cit,

p.458.

Stonor (Pishill)

(NOT ON FINAL VERSION OF TRACK)

"Warmscombe Lane, on verge"

(only mention 1957):

Although it would have

fit the alignment from Stonor, being 1½ miles south-west of it, this stone

didn't make it into the final itinerary of boulders on the Track. Possibly

this was because Rudge was told about it, but never confirmed its existence

(although that never seemed to bother him before.) The map reference given,

SU723877, places it along an unsurfaced public byway (often just a muddy

bridleway) called Warmscombe Lane. This tree-lined and in some places

deeply-sunken track forms part of the boundary between Pishill with Stonor

and Bix and Assendon parishes, and is also likely to have been the boundary

of an 8th century Anglo-Saxon estate called 'Readonora', which

included Stonor.

Stonor (Pishill)

(NOT ON FINAL VERSION OF TRACK)

"Warmscombe stone, at side

of lane" (first mention 1950):

A second stone was recorded

along Warmscombe Lane, but three-quarters of a mile further to the

south-east. This and the two stones that follow seem to have been part of

the "hitherto obscure section" mentioned above, leading towards Henley (B -

D on the map.) They need to be dealt with before returning to the 'Lost

Trackway' version of the route heading south-west from Stonor. Although

Rudge never saw the first Warmscombe stone, he may have seen the second, at

SU731870, where "on the highest point commanding a view across the valleys

on each side, is a large puddingstone in the hedgebank".1

1. Letter from Dr. Rudge

in 'The Bucks Examiner' 1/9/1950, p.4.

Bix Bottom

(Bix & Assendon) (NOT ON FINAL VERSION OF TRACK)

"Bixbottom Farm" (first

mention 1950):

Since Rudge went there in

the summer of 1950, the farm has become Valley or Valley End Farm

(SU72778667), and is now home to various business units and workshops. This

is about 400m south-west of the previous boulder. "Here again", he said, "I

found conglomerate stones in the farmyard".1 However, by the time

of his 'Essex Naturalist' paper read in 1951, it had become "At entrance to

farm".2 There are no boulders visible in the yards today, nor at

any of the entrances.

1. Letter from Dr. Rudge in

'The Bucks Examiner' 1/9/1950, p.4.

2. E.A. & E.L. Rudge:

'The Conglomerate Track' in 'Essex Naturalist' Vol.29, part 1 (March 1952),

p.28 (read 24/11/51.)

Henley-on-Thames

(NOT ON FINAL VERSION OF TRACK)

"At junction of roads"

(only mention in print 1950; read 1949):

Rudge said that "a very typical markstone stands at the corner of the

junction of the Marlow-Henley-Nettlebed roads".1 The map

reference he gave was fairly close, but the exact spot would be

SU7602883075, almost three miles south-east of Bix Bottom. This was and is

the only actual 'corner' where Marlow Road, Fair Mile (from Nettlebed) and

Northfield End meet. This puddingstone, like many others, has gone, and I

haven't been able to find a photograph when it was in situ.

While

attempting to track down this object I came across another puddingstone in

Henley, tucked away in a small public garden about one-third of a mile to

the south-west. The garden is sandwiched between West Street and Gravel

Hill, at their western ends. The stone isn't very large, but has the

slightly conical shape that Rudge saw as being a 'typical markstone', so I

wondered if it had been transplanted there from the junction. I made

enquiries of the Henley Archaeological & Historical Society and the town

council, but neither knew anything about where the Gravel Hill stone had

come from, or when it was placed there. I later found that it had been

rescued from a demolished inn, which a local woman then persuaded the

Borough Surveyor to incorporate into the garden.2 Of Rudge's

stone, I have been unable to discover anything more. While

attempting to track down this object I came across another puddingstone in

Henley, tucked away in a small public garden about one-third of a mile to

the south-west. The garden is sandwiched between West Street and Gravel

Hill, at their western ends. The stone isn't very large, but has the

slightly conical shape that Rudge saw as being a 'typical markstone', so I

wondered if it had been transplanted there from the junction. I made

enquiries of the Henley Archaeological & Historical Society and the town

council, but neither knew anything about where the Gravel Hill stone had

come from, or when it was placed there. I later found that it had been

rescued from a demolished inn, which a local woman then persuaded the

Borough Surveyor to incorporate into the garden.2 Of Rudge's

stone, I have been unable to discover anything more.

1. E.A. & E.L. Rudge:

'Evidence for a Neolithic Trackway in Essex' in 'Essex Naturalist' Vol.28,

part 4 (March 1950), p.180 (read 29/10/1949.)

2. Letter from Ms. J.

Morgan to Mrs. R. Pilcher, 22/8/1982.

'Confirmatory

evidence' (NOT ON FINAL VERSION OF TRACK)

"A well-defined track"

(only mention in print 1950; read 1949):

Shortly after his first talk on the subject, Dr. Rudge told his

correspondent Mrs. Pilcher that information gained "not from actual

observation, but from old records" indicated that, after St. Albans, his

Track went on "still further by way of Chesham, Denner Hill, Henley, Goring,

and possibly to Avebury".1 Nine months later he was convinced,

after various field trips, that beyond Goring it continued south-westwards

through Streatley, Aldworth, Chievely and Hungerford in Berkshire, then to

Ramsbury and Ogbourne St. Andrew in Wiltshire, perhaps even passing through

Avebury and on to the chalk downs of North Wessex.2

His

evidence for this was immediately west of the Henley puddingstone, where

what he called "a well-defined track aligned on Streatley, on the River

Thames, passes through the site of a moated mound".3 The first

part of this track has to be what is known as Pack and Prime Lane, a

bridleway that starts about a third of a mile south-west of the stone's

former location. In Rudge's time, and until recently, it was thought to have

been part of an ancient route recorded in 1353 as a 'via regia' or

'royal way' from Henley to Goring.

More recent research suggests that Pack and Prime Lane is actually a later,

and secondary, medieval route, not part of the original 'royal way'. The

earlier line may well have been a more southerly path, by way of Greys Lane.

Both meet near the beginning of a track called Dog Lane which, beyond

Rotherfield Peppard, becomes Wyfold Lane. But then, the 'via regia'

completely abandons Rudge's westward alignment, diving south-west across

Goring Heath, and approaching Goring from the south-east through Gatehampton.

While parts of the 'royal way' are likely to be late Anglo-Saxon in origin,

other parts are more probably medieval - there is certainly nothing to

suggest that any of it is prehistoric.4 The only 'moated mound'

that Rudge could be referring to is a probable Bronze Age bowl barrow, with

faint traces of a ditch round it, just south of Rotherfield Greys (at

SU72688161.) But this is 350m south of the old route, and too late in

prehistory for Rudge's Track.

By

mid-1951 this was all forgotten anyway, as Rudge had by then concluded that

his Track crossed the Thames at Pangbourne, not at Goring, and its direction

after Stonor was completely reimagined.5

1. Letter from Dr. Rudge to

Mrs. R. Pilcher, 23/11/1949.

2. Letter from Dr. Rudge to

Mrs. R. Pilcher, 28/9/1950.

3. E.A. & E.L. Rudge:

'Evidence for a Neolithic Trackway in Essex' in 'Essex Naturalist' Vol.28,

part 4 (March 1950), p.180 (read 29/10/1949.)

4. R.B. Peberdy: 'From

Goring towards Henley: The Course, History and Significance of a Medieval

Oxfordshire Routeway' in 'Oxoniensia' Vol.77 (Oxfordshire Architectural &

Historical Society, 2012), p.91-105.

5. Letter from Dr. Rudge

to Mrs. R. Pilcher, 18/6/1951.

Bix Bottom

(Bix & Assendon)

"Page's Farm, by gate"

(first mention 1957):

Returning to the 'final

version' of the Track - now simply a private residence, Pages Farm

(SU72028775) is in a very isolated spot at the end of a long, narrow and

badly-maintained by-way that winds between the hills just south of Warburg

Nature Reserve. It stands about 1¾ miles south-west of Stonor House. Here

was said to be "a broken boulder, one piece resting by the farmyard gate".1

A new driveway and entrance to the house have been made since Rudge's time,

in a different location, and I couldn't find any fragments of puddingstone

nearby in 2017.

1.

E.A. Rudge (ed.

John Cooper): 'The Lost Trackway' (1994), p.20.

Nettlebed

"Nell Gwynne's Bower,

Soundess House" (first mention 1957):

Footpaths lead south-west

from Pages Farm for two-thirds of a mile, past the entrance gates to

Soundess House. This is essentially a 19th century building, with no

evidence on site of an earlier one, but seems to be a successor to a mansion

owned by the Soundy family, known there in the 13th century. In the grounds

just south of the house, at SU71098718, is a feature known as 'Nell Gwynne's

Bower'. Dr. Rudge termed it a 'listed ancient monument', describing it as "a

small enclosure surrounded by tall yew trees. Within it lies a group of

boulders two of which are large conglomerates".1 In 'Lost

Trackway' he further explained it as consisting of "some very large

boulders, some of sarsen and others of conglomerate, in a quadrilateral

enclosure".2

Local tradition claims that

Nell Gwyn, mistress of King Charles II from 1668 to his death in 1685, lived

- or at least stayed - at Soundess, although the story is unproven. Another

tale says that she was buried in the Bower named after her, despite the fact

that her burial place is known to be within a London church. Rudge of course

thought that the spot could claim "a much greater antiquity." Unfortunately,

no illustrations of it seem to exist, and the grounds of Soundess are not

open to the public. By itself, the Bower is not and never has been a 'listed

monument'; it's merely included with the house as Oxfordshire HER No.2097.

The archaeological field notes on this entry simply say "Nell Gwynne's Bower

comprises ancient yews planted along three sides of a rectangle 18m by 11m.

In the area so contained are a few sarsens and pudding stones. A folly

rather than an antiquity."

1. E.A. Rudge: 'The

Puddingstone Track' in 'Essex Naturalist' Vol.30 (1957), p.55.

2.

E.A. Rudge (ed.

John Cooper): 'The Lost Trackway' (1994), p.8.

Nettlebed

"Roadside verge, at corner

of by-road" (first mention 1957):

Another half a mile to the

south-west reaches the village of Nettlebed. From the High Street, a road

called 'The Green' runs east to join with the road (Crocker End) that runs

past Soundess. A puddingstone "inset into the road bank" was found by Rudge

"at the corner of the lane leading to the Congregational Church, at the

junction with the lane from Soundess House".1 The lane to the

church (now a private house) is Chapel Lane, which has two entrances from

the north side of The Green. Luckily the map reference given by Rudge in

1957 enables me to pinpoint the corner as SU70318684, the eastern entry of

Chapel Lane. There are actually no 'road banks' at either entrance now, and

although there are small pieces of rock spaced all along the verges, none

are puddingstone, and all are clearly placed there to keep vehicles off the

grass. It should be noted, though, that puddingstones in the Nettlebed area

are not at all rare; they can apparently be found scattered across the woods

and commons surrounding the village.

1.

E.A. Rudge (ed.

John Cooper): 'The Lost Trackway' (1994), p.20.

Nettlebed

"The Bull Inn, High Street"

(first mention 1957):

The name of the inn and its

location were all that were given in that first mention of 1957. Then in

1962, Lilian Rudge said "only last September we found a very fine specimen

in the coaching yard of the old Bull inn at Nettlebed, Oxfordshire, which is

now listed as of historical importance by the British Museum".1

The discrepancy in dates is only cleared up in 'Lost Trackway', where Dr.

Rudge said that "A second stone is within the coaching yard, seen in

1961." Misnaming the pub as the 'Bell Inn', he added that the first

puddingstone "stands outside the coach entrance and beneath the bar window."

The Bull was closed in

1991, and is now private housing at Nos.19-23 on the south side of the High

Street (SU70058678, 185m west of the Chapel Lane corner.) The present

building is of the early 18th century and later, but an inn by that name was

known in the village in the 1600s. A hostelry of that date, and on a major

route halfway between Henley and Wallingford, would naturally be a coaching

inn, and it has a tall (but not particularly wide) archway leading to its

courtyard.

Only

125m to the east is a small circular grassy area, a detached part of the

larger Green, with a public shelter upon it. There, along with an

information board, are two puddingstones that were both supposedly

found in the courtyard of the Bull, and moved here when it was closed. Once,

the board used to display information directly based on Rudge's Track

theory, and even contained the line "This stone is known and registered in

the British Museum as a 'pudding stone'." Research later showed that the

Museum knew nothing about the stones, and the county archaeologist cast

doubt on the trackway notion, so the old board was discarded. I measured the

larger of the stones on the Green at 1.1m x 90cm x 50cm high, while the

other is 62cm x 53cm x 50cm in height. Only

125m to the east is a small circular grassy area, a detached part of the

larger Green, with a public shelter upon it. There, along with an

information board, are two puddingstones that were both supposedly

found in the courtyard of the Bull, and moved here when it was closed. Once,

the board used to display information directly based on Rudge's Track

theory, and even contained the line "This stone is known and registered in

the British Museum as a 'pudding stone'." Research later showed that the

Museum knew nothing about the stones, and the county archaeologist cast

doubt on the trackway notion, so the old board was discarded. I measured the

larger of the stones on the Green at 1.1m x 90cm x 50cm high, while the

other is 62cm x 53cm x 50cm in height.

Examining

the frontage of the Bull, a patch in the pavement can be clearly seen where

the first stone once stood, to the left of the archway and close to the bay

window of the bar. What Rudge never mentioned is that there is the jagged

stump of another puddingstone on the opposite side of the arch.

Painted white, it looks as if the bulk of it has been broken off, and it now

measures 25cm x 15cm x 40cm high. During research I came across a black and

white photograph of the Bull Inn dated c.1955, which shows both of these

stones in situ. It's hard to be certain, but the one to the right looks

taller than that on the left, and more of it is intact, jutting out a little

into the archway. Examining

the frontage of the Bull, a patch in the pavement can be clearly seen where

the first stone once stood, to the left of the archway and close to the bay

window of the bar. What Rudge never mentioned is that there is the jagged

stump of another puddingstone on the opposite side of the arch.

Painted white, it looks as if the bulk of it has been broken off, and it now

measures 25cm x 15cm x 40cm high. During research I came across a black and

white photograph of the Bull Inn dated c.1955, which shows both of these

stones in situ. It's hard to be certain, but the one to the right looks

taller than that on the left, and more of it is intact, jutting out a little

into the archway.

Then I spotted another

photo of the same era, but taken from the opposite direction, which to my

surprise revealed that there was a third puddingstone present. This

had also been painted white, and was standing - possibly loose on the

surface - against the left hand edge of the archway, close to the first

stone. Further research uncovered the recollections of an inhabitant

regarding the Bull in a local newspaper: "Laureen remembers that the Bull

was a very popular pub but was difficult to access by car due to the narrow

entrance and a pudding stone".2 Since neither of the stones on

the left impinged upon the entrance, it must have been that on the right

that caused problems. An attempt may have been made to remove it whole but

it broke in the process, or perhaps the protruding part was simply smashed

away. Presumably one of the others was then taken into the courtyard, where

the Rudges found it in 1961.

1. Lilian Rudge: 'Mystery of

the Stones' in 'Essex Countryside' Vol.10, No.68 (Sept. 1962), p.469.

2. 'When village bustled

with pubs and shops' in the 'Henley Standard', 31/10/2011.

Witheridge

(Stoke Row)

"Stoke Row stone" (first

mention in print 1952; read 1951):

This puddingstone, about

two miles SSW of Nettlebed, featured in three of Rudge's published works,

but the first two, in 1952 and 1957, gave no more information than a map

reference: SU690841. This location is beside or near the road from Highmoor

Cross to Stoke Row, and about halfway between the two. Dr. Rudge mentioned

the stone to Mrs. Pilcher in 1950, saying "there is a real beauty, with a

legend, at Stoke Row".1 In 'Lost Trackway' he admitted that,

after Nettlebed, "the route is not clearly defined, and it is not until

Stoke Row is reached that a huge stone at Witheridge is found. This is the

object of a legend, and obviously an ancient landmark." (Witheridge is a

small community of a pub and a few houses on a hill of that name, on the

road from Highmoor Cross.)

Then, in the only available

history of the area I read the following: "Quite a few puddingstones are to

be found in this locality....There is a very large one on the right hand

side of the hill as you go from the bottom of Witheridge Hill up to Stoke

Row".2 Rudge's coordinates

were

very nearly correct, as this stone can be found at SU6910684123, about

halfway between Clare Cottage and the Witheridge crossroads. It's just

within private (unfenced) woodland, but only about five metres from the

north side of the road. The stone (conglomerate, not true HPS) is deeply

embedded, with the visible portion measuring 1.7m x 1.5m x 50cm high. As far

as the 'legend' goes that Rudge referred to, he never gave any details, and

I can find no record of it. However, I suspect it was a misunderstanding of

the following: "Bill George told me that in the early days of this century

[the 20th] several local men tried to put chains around this rock in order

to pull it out, using the power of a steam engine, 'but it wouldn't budge an

inch - I reckon it goes down very deep, like an iceberg'".3 This

probably mutated into the folklore attached to many large stones, that it

was 'immovable'. (The same tale appears in one of the author's other books,

a historical novel set in the Stoke Row area.4) were

very nearly correct, as this stone can be found at SU6910684123, about

halfway between Clare Cottage and the Witheridge crossroads. It's just

within private (unfenced) woodland, but only about five metres from the

north side of the road. The stone (conglomerate, not true HPS) is deeply

embedded, with the visible portion measuring 1.7m x 1.5m x 50cm high. As far

as the 'legend' goes that Rudge referred to, he never gave any details, and

I can find no record of it. However, I suspect it was a misunderstanding of

the following: "Bill George told me that in the early days of this century

[the 20th] several local men tried to put chains around this rock in order

to pull it out, using the power of a steam engine, 'but it wouldn't budge an

inch - I reckon it goes down very deep, like an iceberg'".3 This

probably mutated into the folklore attached to many large stones, that it

was 'immovable'. (The same tale appears in one of the author's other books,

a historical novel set in the Stoke Row area.4)

It probably would have

messed up the line of his Track if Rudge had known about the other

puddingstones not far away, to the south-east in Greyhone Wood and

north-east near Bromsden Farm. Not to mention the fact that all these stones

were probably dug up from the numerous old chalk-pits that used to dot the

landscape hereabouts.

1. Letter from Dr. Rudge to

Mrs. R. Pilcher, 28/9/1950.

2. Angela Spencer-Harper:

'Dipping into the Wells' (Robert Boyd Publications, 1999), p.5.

3. Ibid.

4. Angela Spencer-Harper:

'The Old Place' (Robert Boyd Publications, 2007), p.22-3.

'Confirmatory

evidence': Rotherfield Peppard flint mines:

Just over two miles

south-east of the Stoke Row stone is the village of Rotherfield Peppard,

where Rudge was keen to point out "a small area of flint mines" was

excavated in 1912 by A.E. Peake.1 This was at SU71008143, on

Peppard Common. In 'Lost Trackway' Rudge commented that "These mines were

never of great importance, and not to be compared with Grimes Graves, but

they were significant in one respect, that they contributed to the

meaning of the trackway [his italics], as I shall later describe".2

Unfortunately, there was to be only one more page and an epilogue in his

book, and he never did describe the meaning intended.

Considering their location,

these mines would have made more sense as evidence on his earlier supposed

route heading west from Henley-on-Thames, as they sat virtually on the old

'via regia' to Goring. However, they have since been reassessed by

archaeologists, and it seems now very unlikely that they were mines at all.

According to Miles Russell, "a number of Neolithic surface finds, possibly

related to flint working, have been recorded, but no conclusive evidence for

the existence of actual mines has yet been found".3 Barber, Field

and Topping classed it as "a depression containing much debitage...once

thought to be a quarry or mine".4 (Debitage includes all the

tools, blades, chips and flakes created during the working of flint.)

1. A.E. Peake: 'An Account

of a Flint Factory...at Peppard Common' in 'The Archaeological Journal'

Vol.70 (Royal Archaeological Institute, 1913), p.33-68.

2. E.A. Rudge (ed. John

Cooper): 'The Lost Trackway' (1994), p.20.

3. Miles Russell: 'Flint

Mines in Neolithic Britain' (Tempus Publishing, 2000), p.54.

4. M. Barber, D. Field &

P. Topping: 'The Neolithic Flint Mines of England' (English Heritage, 1999),

p.31.

***********

After Stoke Row, Dr. Rudge

was never entirely sure of the direction that his Track then took. As stated

earlier, by mid-1951 he had become confident that it crossed the river

Thames at Pangbourne, rather than at Goring. He sent out letters to

newspapers in Newbury, Basingstoke and Alton asking for any information

about puddingstones in those areas. The results led him to believe - for a

while at least - that perhaps the Track was heading south into Hampshire,

and not for Avebury after all.

At some point he

received word of an actual puddingstone boulder at Pangbourne, 6¼ miles SSW

of Stoke Row, and so, tentatively, plotted the Track's course onward into

Berkshire. Of the next and final ten stones listed, eight were never

actually seen by him. I think it's entirely possible that he never saw the

other two either. This final stretch covers 32 miles across Berkshire and

just nudging into Wiltshire, and is purely speculative on the part of Dr.

Rudge.

Berks & Wilts

►

Back to Contents ► |