|

Hidden East Anglia: |

The Puddingstone Track: Deconstructed |

|

|

Puddingstone Track Deconstructed: |

About Dr. Rudge, and about Puddingstone

About Dr. Rudge:

Ernest Albert Rudge was born in 1894.

According to the journal 'Nature' in 1934, he "graduated B.Sc. (London) with first class honours in chemistry in 1915, and thereafter was engaged as an analytical chemist first at Messrs. Johnson and Sons, at their smelting works [at Brimsdown, now in the London Borough of Enfield], and then as an analytical and research chemist in the Osram Robertson Lamp Works [at Hammersmith]. Since 1930, Dr. Rudge has made a special study of the uses and behaviour of timbers in South Wales industries, and of the causes and circumstances of decay in industrial timbers."

In addition to his B.Sc, he had an M.A. and a Ph.D, was a Fellow of the Royal Institute of Chemistry, and an Associate Member of the Institute of Chemical Engineers. As he himself said, he was "trained as a teacher, and a teacher of Chemistry." After being a lecturer in applied chemistry and chemical engineering at Cardiff Technical College, by 1938 he was Head of the Department of Science at West Ham Municipal College. By 1946 he had been appointed Principal of what would later be renamed as West Ham College of Technology.

An amateur archaeologist and photographer, he was elected a Member of the Essex Field Club, also in 1946, and in 1958 founded the still-active West Essex Archaeological Group. Apart from many articles and reviews in professional journals and popular magazines, the only published work of his that I could find was a small paperback entitled 'Simple Home Chemistry for Boys' (Vawser & Wiles, London, 1943.) He and his wife E.L. Rudge (a Fellow of the Zoological Society, and always known as Lilian) had two sons, who became a mechanical engineer and a physicist.

Dr. Rudge retired in 1959, and died in 1984, at or near the age of 90.

Rather than begin a quarter-century quest for a long-distance prehistoric trackway marked by puddingstones, Dr. Rudge's initial intention was quite different. He wanted to examine Alfred Watkins' 1921 theory of the 'Old Straight Track' (ley lines) as it applied in Essex. He actually wasn't that enamoured of the theory and soon forgot all about it, but it served as the inspiration to look for 'monoliths' that might be sighting points. Consulting A.E. Salter's 1914 list of 'erratic boulders', he decided to ignore sarsens, as they were too numerous and prone to be moved in modern times. He therefore settled on looking for conglomerates since they occurred less frequently, and were, as he said, "easily recognisable".

The puddingstone by the roadside in Holyfield hamlet was on Salter's list, and as Rudge lived then near the western edge of Epping Forest, it was the closest for him to check out. It was there that he heard about other nearby boulders, which he claimed at various times were "in an almost straight line." Given that he never actually located two of them, this claim remains unproven. It nevertheless led him to project this rough alignment further to the east and north-east, which took him on his initial quest for puddingstones across the rest of Essex.

About Puddingstone (and other relevant rocks):

"Every stone of the series was a 'puddingstone', a name which aptly describes its appearance..."

"Above all else, every boulder was of the easily recognisable pebbly conglomerate."

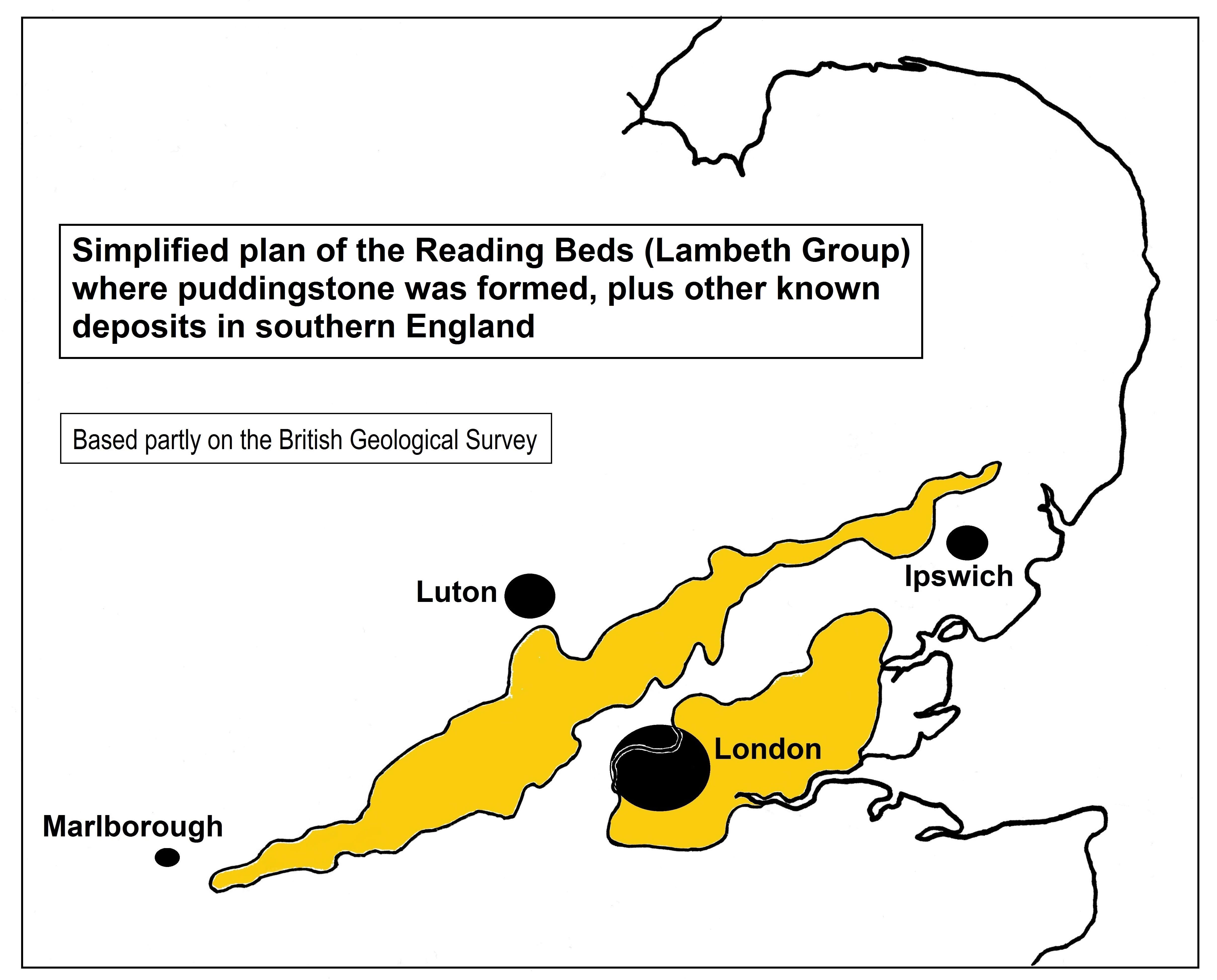

As the quotes above show, although Dr. Rudge was often somewhat flexible in his use of the word 'puddingstone', he rightly used the catch-all term 'conglomerate' when necessary. There are different types of puddingstone, and many different types of conglomerate. 'True' puddingstone is that mainly found in (and named after) Hertfordshire, but it can also be found to the east and west of that county. About 55-56 million years ago, much of south-eastern England lay beneath a shallow sea. The coastline ran through the middle of Norfolk and Suffolk, turned south-west through Essex and Hertfordshire, then curved down through Berkshire and Hampshire, to the Southampton area. A dense layer of sand and gravel was laid down on top of the chalk, once known as the Reading Beds (nowadays classed as one of the formations in what is called the Lambeth Group.) Later these deposits were raised above sea level, where ground water allowed dissolved silica (quartz) to penetrate the sand, forming a hard layer of sandstone. The hardest variety is known as sarsen, and into this was sometimes mixed stones of flint or chert from the underlying pebble beds, forming a conglomerate rock which came to be called Hertfordshire Puddingstone. Over the following millions of years geological upheavals, river erosion and glaciation brought it closer to the surface in some areas as outcrops, at the same time breaking up the hard layers and leaving boulders strewn across the landscape. Very little now remains in situ, having been mostly quarried away for building material, or in Iron Age and Roman times, for making quern-stones for grinding grain.

Hertfordshire Puddingstone (HPS) contains rounded, brownish flint pebbles up to 5cm across, bound with silica in the sandstone matrix. When split, the fracture passes through the pebbles rather than around them, as both flints and matrix are of the same hardness. Bradenham Puddingstone is a localised variant found in Buckinghamshire. There, the pebbles tend to be paler, larger and more angular.

Sarsen is of the same composition and hardness as puddingstone, but without pebbles (although there is an occasional 'transitional' example.) Both are known as silcretes.

There are many other types of conglomerate, much younger in geological age than HPS: rough masses of flint or other pebbles, generally angular, poorly cemented together by various minerals including calcium carbonate and these, sometimes known as calcretes, can be found in many different areas.

Ferruginous conglomerate or ferricrete, common in Essex and Suffolk, appears in various shades of brown, as the stones within are bound in a matrix rich in iron oxide. These tend to be small and angular, often more like shards of gravel rather than pebbles.

The carstone (or carrstone) of north-west Norfolk is similar, but the sandstone is softer, and the colour can range from pale orange to chocolate. Most carstone doesn't contain any visible pebbles - and thus isn't actually a conglomerate - but the variety that does is sometimes colloquially known as puddingstone.

All of these rougher varieties of conglomerate, and more, Rudge accepted as 'puddingstone' along the length of his Track, especially in Suffolk and Norfolk. Some, unfortunately, had no visible pebbles in them at all.

|

|