|

Hidden East Anglia: |

The Puddingstone Track: Deconstructed |

|

|

Puddingstone Track Deconstructed: |

Along the Track: BUCKINGHAMSHIRE

Part 2: St. Mary's church, Chesham

"Church built on puddingstone circle" (first mention in print 1952; read 1951): St. Mary's, the parish church of Chesham, stands at SP95660152, off the north-west side of Church Street. This is about 250m WNW of where the 'Market Stone' would have stood.

In his first paper on the Track, read to the Essex Field Club on October 29th 1949, Dr. Rudge said that "Very recently we have discovered conglomerate boulders under the buttresses of Chesham Church and in Chesham churchyard". (He actually 'discovered' this by reading about it; but there are actually none in the churchyard.) I have to assume that his follower-to-be Mrs. Pilcher attended that talk, as only ten days later he wrote to her "Some day I am hoping to trace this new track across Hertfordshire to Chesham and beyond".1 He had yet to visit the town, but had already determined the hoped-for course of his Track.

In February 1950 he made his first visit, and sent Mrs. Pilcher a thumbnail sketch of the church. That sketch showed the building as a '+' shape (which it is not), and marked puddingstones at almost every corner. He added the note: "Stones arranged under cruciform buttresses with small stones in angles. Suggests stone circle originally".2

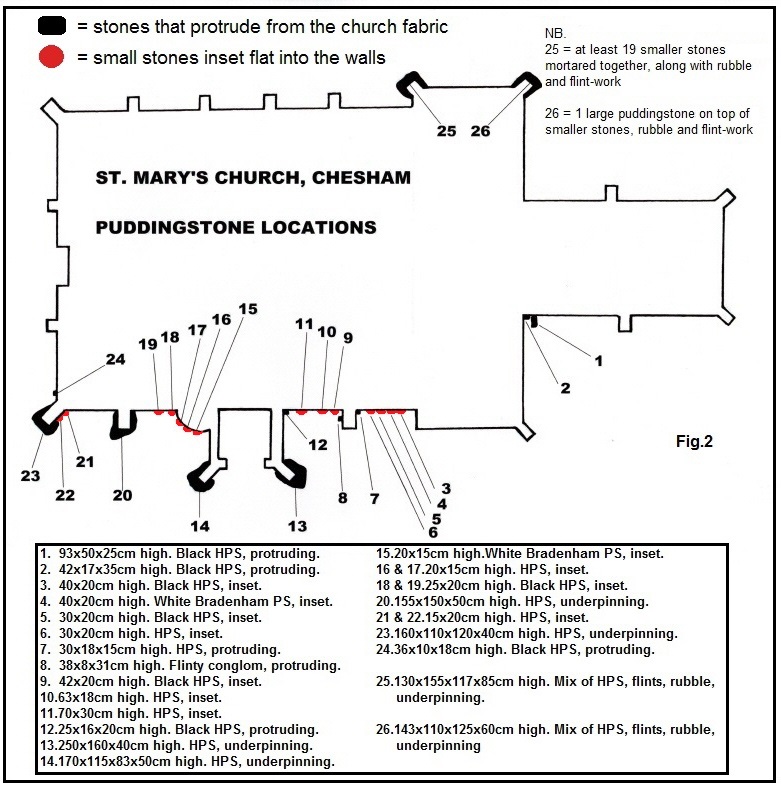

Fig.1 above is a comparison of Rudge's sketch to an actual plan of the church showing the major puddingstone locations.

By July he was broadcasting this theory in the local newspaper.3 Then in September 1951 he brought Field Club members to the town, where "Dr. Rudge surmised that they [the stones] were the recumbent remains of a pagan stone circle, and vividly illustrated this point by saying that if the church were lifted up, the puddingstones would be seen to be in the shape of a circle, the diameter of which he had measured".4

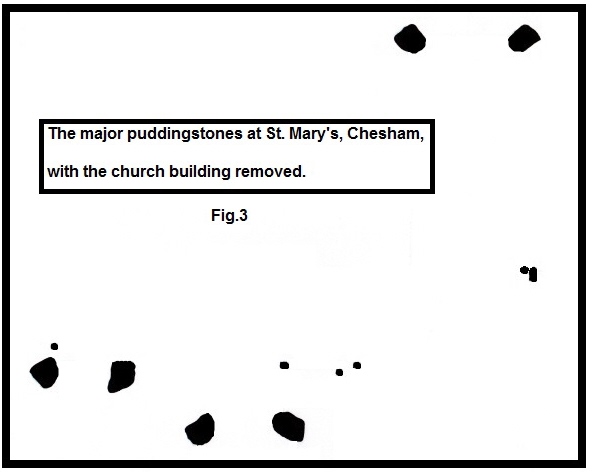

He formalised this two months later when he read his second paper to the Field Club, where he said that St. Mary's "stands upon a group of not less than sixteen large puddingstone boulders which originally stood in a great circle...If in imagination one removes the Church from the site, the remarkable character of this prehistoric feature is apparent. In its original form it consisted of sixteen or more conglomerate boulders, varying in size from three feet to eight feet or more in length, set in a circle about 100 feet in diameter".5

That there were large puddingstones under some of the buttresses was already known, despite Rudge's statement that "no-one seems to have noticed them before".6 The Royal Commission on Historical Monuments mentioned them in 1912, in their Inventory for Buckinghamshire. In the same year, they were noted in a volume on the county by the palaeontologist A. Morley Davies.7 In 1925 the Victoria County History recorded buttresses resting on "unhewn pudding-stone." Rudge may indeed have been the first in print to suggest a former stone circle - although without using those words, there is a 'Souvenir of Chesham' postcard dated to about 1905 which bears the legend "Tradition says it [the church] is built on a site where originally stood a temple of the Druids."

Unfortunately, the myth of the 'stone circle' at Chesham is now widespread. It appears online, in the church leaflet, guide books for both town and county, countless other books and magazine articles, and in the Wikipedia entry. If it had existed it would be unique, as there is no known prehistoric stone circle anywhere in Buckinghamshire.

*********** The specific claims made by the Rudges need to be examined in detail. Lilian Rudge wrote in 1957: "Here we found the church at Chesham built upon a mound, with a total of at least 19 puddingstones of huge size under the foundations of the buttresses. Apart from those on the north wall, which had been heaped together when the north wall was rebuilt in the C15th, these stones when plotted lay in a large circle in their original positions".8

According to Dr. Rudge in 'Lost Trackway': "under every corner and every buttress was a large puddingstone, resting in the now familiar position on the foundation layers. It is a cruciform building, and the stones were under the quoins of the transepts, making in all an almost complete stone circle".9

Unfortunately, this is all rather wrong. Firstly, St. Mary's church isn't actually built on a mound. It stands on the lower slopes of a hill that rises gradually from Church Street, and continues rising as it goes north-west, becoming the ridge on which the little village of Chartridge sits, a few miles away.

Chesham church has 19 buttresses, and there are puddingstones under only 6 of them. There are no stones under any of the other corners, and the only quoin on any of the transepts has no stone beneath it. The two buttresses on the north transept have puddingstones underpinning them, but they are a mix of large and multiple smaller puddingstones, flint-work and other rocks, each cemented into a single 'block'. Rudge believed that these were the missing stones from the other buttresses, which had been heaped together when the north wall of the nave was rebuilt in the late Middle Ages. Actually the entire nave was rebuilt in the 13th century, but at the same time both the north and south aisles (outside the nave, where the stones are) were added. Since puddingstones were clearly built under the south aisle, there's no reason I can see that they couldn't have been incorporated into the north aisle as well.

My opinion is that the large boulders were placed there for aesthetic reasons. The south is the side of the church seen from the town, and the side from which it is entered. For example, there are many small chunks of puddingstone, all about the same size and inset into the walls just above ground level, clearly for decorative purposes - and they are all in the walls on either side of the south entrance porch.

Fig.2 below shows a detailed plan of the church with the location of every puddingstone, plus dimensions and composition.

I've photographed, measured and plotted every puddingstone at St. Mary's, and can find no evidence that they were ever part of a circle about 100 feet (30.5m) across, as Rudge claimed. According to him, "Those on the southern side are still in situ, though overthrown". But even if we were to ignore all the rebuilding and reconstruction of virtually every wall which occurred between the 13th and 15th centuries, there are two very large boulders underpinning the buttresses of the south porch, which didn't even exist until the 15th, so cannot be in situ. The other six small rocks that protrude from the fabric are far too small to have ever formed part of a stone circle, leaving only two large boulders on the southern side. (Photographs of every stone can be found at the foot of this page.)

Examining the two heaps of different stones cemented together under the north transept buttresses, it's possible to discern two, possibly three, that might approach the size of those underpinning the southern side. At the most, that results in a grand total of seven boulders (not "sixteen or more") from which Rudge constructed a hypothetical stone circle of prehistoric age. The notion that if the church were 'lifted up' such a circle would be visible is, quite frankly, nonsense, as Fig.3 below demonstrates. (The inset decorative pieces are omitted, and the jumble of rocks at the north transept buttresses are each shown as if they were single stones.)

The alleged circle at Chesham was always Rudge's "most sensational discovery...It was probably the centre of the ancient tribal culture and is without doubt much older than Stonehenge. With the coming of Christianity the stones were overthrown and the earliest church at Chesham was built on top of them".10 No one knows when the Saxons came to Chesham, if they were Christian when they arrived, or if they were converted later. Virtually all the present church dates from the 13th century onwards, although a single window of the 12th tells us that it was founded earlier. This is confirmed by a register of 1153 which refers to a church in the town.

Although it's not unlikely, there is no documentary, archaeological or architectural evidence to support an earlier church on the site. If there was, any Saxon church would almost certainly have been made of timber. In which case, the puddingstones would have been totally unsuitable and unnecessary for the foundations or fabric.

The earliest name known for Chesham appears in the will of Ælfgyfu or Elgiva, made between 966 and 975. She is generally accepted to have been at one time the queen consort of Eadwig or Edwy, King Of England for less than four years. In that will Chesham has the Anglo-Saxon name of 'Cæstæleshamm', meaning 'the water-meadow by the heap of stones'. Clearly the Saxons named it for the two most distinguishing features of the locality: the meadows watered by the emerging streams of the river Chess about 200m south-east of the church (now mostly covered by a car park), and the pile of large rocks that was somewhere nearby. The fact that they called it a 'heap of stones' tells us that there was no prehistoric circle there at the time.

In 1951 Rudge informed Mrs. Pilcher that "The Oxford Place-name Dictionary claims it [the name Chesham] is derived from British words meaning the 'ring of rocks on a hill'".11 This is completely untrue. I have both the first (1936) and fourth (1960) editions of that work by Eilert Ekwall, and both give the Anglo-Saxon derivation stated above.

I'm certain that these stones were simply a natural feature of the location, perhaps dragged from the bed of the nearby river. Or gathered from the surrounding land. Or perhaps there was an unrecorded outcropping of puddingstone in the vicinity. There are or were many such stones all over the town, and in the surrounding countryside. (See the next page 'Puddingstones in Chesham'.) As such, they served no function until an early stone church was built there, and were used not only decoratively, but as practical, cost-free and remarkably sturdy masonry supports. As the church was rebuilt and enlarged, it was only natural to keep re-using them - in fact they brought in other conglomerates from elsewhere, as the various types used at the church attest. And I dare say the locals were keen to retain the stones as a key feature of the village that was named after them.

1. Letter from Dr. Rudge to Mrs R. Pilcher, 8/11/1949. 2. Letter from Dr. Rudge to Mrs R. Pilcher, 20/2/1950. 3. 'Neolithic Stones - Interesting point about Chesham Parish Church' in the 'Bucks Examiner', 21/7/1950. 4. 'Reports of Meetings' in 'Essex Naturalist' Vol.29, part 1 (March 1952), p.57. 5. E.A. & E.L. Rudge: 'The Conglomerate Track' in 'Essex Naturalist' Vol.29, part 1 (March 1952), p.21 (read 24/11/51.) 6. Anonymous (with info from Rudge): 'Pudding-stones' in 'East Anglian Magazine' Vol.11, No.5 (Jan. 1952), p.245. 7. Arthur Morley Davies: 'Buckinghamshire' (Cambridge County Geographies, University Press, 1912), p.47, 197. 8. Lilian Rudge: 'The Mystery of the Puddingstone Track' in 'Essex Countryside' Vol.5, No.19 (Spring 1957), p.99. 9. E.A. Rudge (ed. John Cooper): 'The Lost Trackway' (1994), p.6. 10. See No. 6. 11. Letter from Dr. Rudge to Mrs. R. Pilcher, 18/4/1951.

Below: photographs of every puddingstone and conglomerate rock around and in the fabric of St. Mary's church at Chesham.

Stones 1 & 2 Stones 3 & 4 Stones 5, 6 & 7 Stone 8 Stones 9 & 10 Stones 11 & 12

Stone 13 Stone 14 Stones 15,16 & 17 Stones 18 & 19 Stone 20 Stones 21 & 22

Stone 23 Stone 24 Stone heap 25 Stone heap 26

|

|