Wayside & Churchyard Crosses of Norfolk: A Survey

About Crosses

The practice of erecting freestanding upright crosses seems to have occurred mostly between the 9th and 15th centuries - although it may have begun as early as the 4th century in the Celtic areas of Britain and Ireland. To the best of my knowledge, fragments of no more than nine confirmed crosses dating from before or around the Norman Conquest have ever been found in Norfolk. (There are also a number of other pieces that are not so definite, either in identification or in date.)

In broad terms there are only two types of medieval cross: those within a churchyard, and those without. The latter are usually termed 'wayside' crosses, even though they may not stand beside any road or path we know of today. They were erected for a variety of reasons, but due to their obvious Christian nature, they always existed within a religious context, even when their primary usage appeared to be secular.

A cross might be built at the beginning of a lane leading to a church, or act as a way-mark on the route to a priory or other place of pilgrimage. Often they were set up on boundaries between parishes, villages, monastic estates and other property, or to mark the limit of ecclesiastical or political authority. Occasionally they might commemorate an event such as a battle. Medieval wills show that many were built as part of a bequest, so that those who passed by it would pray for the souls of the testator and their family. (Although it should be noted that, just because a will required it, that doesn't mean a cross was ever actually built.) A cross erected in a prominent spot in a village might become the hub for local trade, but the market could also be a focal point for preaching and proclamation. Some may have served multiple roles, either from the beginning, or as over time their original purpose became less significant or was forgotten.

Crosses within a churchyard served to sanctify the ground, act as a memorial to all the dead within, or provide a convenient venue for preaching. As with wayside crosses, some were erected as the result of a bequest. In particular, they were used on Palm Sunday, when churchgoers would be led in procession round the outside of the church, halting at a cross not far from the entrance porch to celebrate Mass before re-entering the building.

The total quantity of such crosses that once populated the landscape will never be known. Even if every will, map and record in existence were to be inspected, an untold number will have gone undocumented. As for physical remains, time, the elements, and landscape development will have disposed of many entirely. Most of those that survive consist of only a pedestal or a section of shaft, or occasionally both together. One of the most complete examples we have is at a crossroads on the parish boundary just south of North Walsham. Even here the capital seems to have been restored in modern times, and the head or cross-piece - which old drawings show as having been an effigy of Christ on the Cross - is now no more than a shapeless vertical rod of stone. Some survive only as fragments which can be hard to identify, while others persist as no more than the name of a crossroads, or the name of a field in a 19th century tithe award.

Many were destroyed or damaged during the iconoclastic purges of the Reformation in the 16th century, and again in the 17th because of Puritanical zeal against religious imagery. The cross-piece was a frequent target for such vandalism, but it wasn't uncommon for hammers to be taken to the shaft as well - although variations in local attitudes meant that occasionally a cross was spared. Sometimes, as at Bressingham in 1549, the churchyard cross was pulled down and its materials sold because the church was in financial need. In the same year, four men were prosecuted for pulling down crosses at Bramerton and Rockland St. Mary. Although they also broke the windows of Bramerton church, it's possible that they were 'cross-diggers', a term for people who went around searching for treasure that they believed might be hidden beneath wayside crosses. Even in the 1980s, Barnham Cross near Thetford was damaged by those similarly hunting for something valuable, and has now disappeared completely.

The Late Saxon Cross:

All the fragments of late Saxon or Saxo-Norman crosses that we know about in Norfolk - dating from the 9th to the 11th centuries - are associated with churches or chapels. In six of these cases only the whole or partial head has survived. All were of the 'round-headed' type i.e. a circular disc of stone with a large, splay-armed cross carved in relief on one or both faces. Three of these were specifically of a kind known as 'wheel-headed', where the quadrants between the cross-arms are pierced through, so that the ends of the arms are joined by a ring or 'wheel'. Other finds have been no more than fragments of shaft with typical Saxon interlace carving. Although a few might have come from tall standing crosses, the prevailing theory is that they may have stood no more than about 1.2m high on a block base, and served as grave markers for prominent people. The same may have been true of the taller and more elaborate cross found in pieces among the remnants of a friary in King's Lynn.

The Medieval Cross:

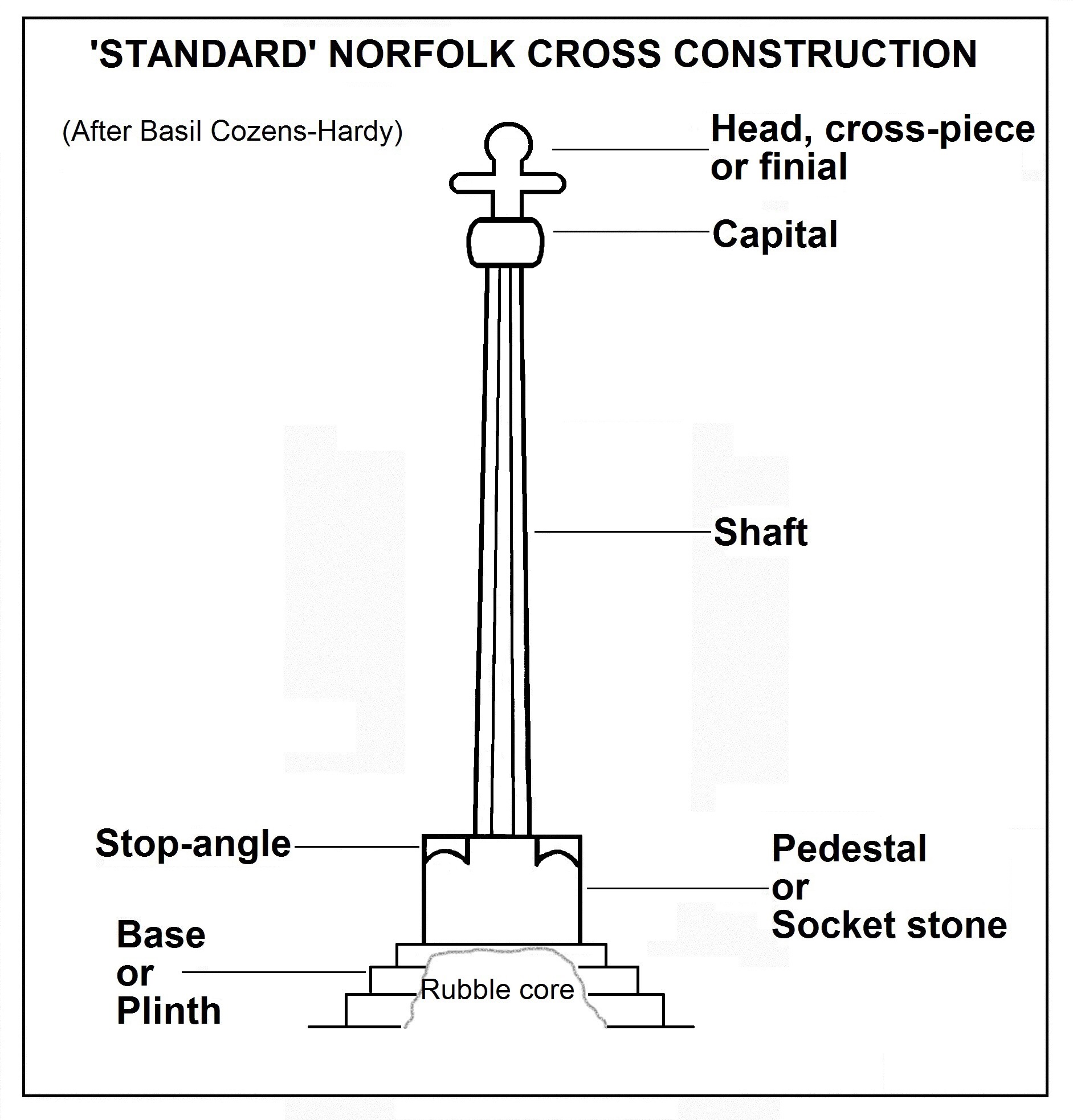

Because of the losses

over the centuries, we can only generalise when it

comes to the structural form of medieval crosses. Although there are

exceptions, the basic form in Norfolk seems to have begun with a foundation

layer of mortared flints or cobbles, now of course lost beneath the soil. On

top of that would be a 'rubble core' of mortared stones around which a base

or plinth would be constructed. This was sometimes a single block, and

sometimes a series of steps, perhaps between three and five in number, which

might be square or octagonal in outline.

outline.

Upon that would sit the pedestal or socket stone, a single square block with chamfered top edges. More often than not, the corners would be carved into vertical bosses known as stop-angles, making the top section octagonal in shape. In the top of the pedestal there would always be a mortise hole, usually square, into which the shaft would be dropped, and fixed in place with mortar, or by the pouring in of melted lead. The shaft itself might be a single block, or in several sections connected with mortise and tenon joints, tapering slightly as it rose in height. Although starting square at the bottom, many shafts were then made octagonal by chamfering the vertical edges. So few have survived intact that it's hard to generalise about their height, but it seems to have been in the range of 1.8m to 3.6m.

On top of the shaft would be a capital, which could be square and blocky, or intricately carved, with a tenon of stone or iron to take the final piece, the head or finial. Fragments of only a handful of these have survived or been recorded from Norfolk. Evidence from other parts of the country suggests that they were usually either a plain cross-piece, or ornately carved representations of the Crucifixion, like the one already mentioned at North Walsham, or the fragment at Reepham which also has other Biblical figures beneath the arms of the cross. A third type - usually in the churchyard - had a 'lantern' shaped structure on top, sometimes called a 'tabernacle', with religious effigies or scenes carved in relief - but as far as I know, this is a type not evidenced in Norfolk.

Most crosses seem to have been made of an easily-carved freestone, specifically limestone. The lightness of the stone, especially when newly-built, would help to explain why so many wayside markers in Britain have the name 'White Cross' - although they could also have been painted with limewash. Decoration of the shaft and pedestal seems to have been fairly minimal in many cases, though some are known to have borne armorial shields, religious iconography, or inscriptions to the memory of the dead.

Unfortunately, not a single one of these crosses still exists in Norfolk in its original, complete form.